Supercharged: Billionaires José E. Feliciano and Kwanza Jones Open Up About Their Philanthropy

Source: Inside Philanthropy

Billionaire couple José E. Feliciano and Kwanza Jones arrived at our interview dressed to the nines in a lush backyard in a fall that only Los Angeles could pull off. With a nearly $4 billion net worth, the couple fly surprisingly under the radar, but they’ve quietly made history in recent years as higher ed donors. The pair met during their undergraduate days at Princeton in the early 1990s and, in 2020, made a $20 million contribution that got two dorms named in their honor — becoming the largest Latino and Black donors in the university’s nearly three-century history.

Born in Puerto Rico, José Feliciano got his start at Goldman Sachs and went on to cofound Clearlake Capital, a private equity firm headquartered in Santa Monica, California, with more than $90 billion in assets under management. Jones is an artist and founder and CEO of motivational media company SUPERCHARGED by Kwanza Jones.

In October, the couple came back into the spotlight with another higher ed gift, $6 million to Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in New York City, where Jones earned her law degree. The donation will establish the Kwanza Jones and José E. Feliciano Program for Clinical Education, expanding access to legal services for underresourced communities while training the next generation of public interest lawyers.

Beyond Princeton and Cardozo, their broader giving flows through the Kwanza Jones & José Feliciano Initiative, which blends traditional philanthropy with impact investing in both nonprofit and for-profit ventures. Guided by four pillars — education, entrepreneurship, equity and empowerment — the initiative takes what Jones calls an “impact supercharged” approach, combining capital with culture, community and capacity-building to amplify results.

Throughout our conversation, Jones and Feliciano described their philanthropy as an extension of their shared values. I found out more about the forces behind their recent gift to Cardozo, how they feel about their historic gift to Princeton, how they blend conventional and unconventional giving, and where they see their philanthropy heading next.

Early influences, small acts of giving, and a philosophy that would later scale

Feliciano’s formative lessons in philanthropy took place on the island territory of Puerto Rico, home to over 3 million people. He remembers his mother watching UNICEF commercials and then immediately rushing to get her checkbook. That simple ritual taught him that storytelling matters. A compelling narrative gets people invested and that can galvanize giving. “In today’s world, I would translate it to, she wanted to see the impact of her philanthropy, which is kind of interesting, because now, obviously a lot of people talk about impact philanthropy… that was what really motivated her and moved her when she saw those types of stories,” Feliciano said.

Born in Los Angeles, Jones also pointed to her parents and the broader family network that raised her. She talked about mutual aid, tithing at church, and the family station wagon that ferried track teammates to meets. “It wasn’t a question of if you were going to give, but what you were going to give,” Jones said. “They [my parents] knew stories we didn’t know. They knew that some of the folks that we were inviting into our homes, didn’t have homes to go to.”

As Feliciano became, in his words, “somewhat wealthy,” those early lessons stayed with him. It didn’t matter how much you had. You could give time, you could give money, and the act of giving back held value in both directions.

A decade ago, when the couple were still in their early forties, they launched the Kwanza Jones and José E. Feliciano Initiative. A rising tide of billionaires were keeping their funding options open by routing it through structures like LLCs and family offices — Jones and Feliciano likewise chose not a traditional private foundation but a hybrid structure that blends nonprofit work with targeted investments.

Feliciano, a veteran investor, views philanthropy through that lens. He looks to invest in organizations that can create catalytic returns, where dollars move through communities and institutions with greater force. “We’re always looking for those multipliers where our philanthropy can generate a disproportionate benefit,” Feliciano said.

Beyond financial support, Feliciano pointed to mentorship as one of the most powerful tools at their disposal. Sometimes, simply seeing someone do something is enough to unlock possibility for the next generation, he said, and create a ripple effect far beyond any individual grant.

How Feliciano and Jones think about their nonprofit and for-profit funding

Jones, who founded SUPERCHARGED by Kwanza Jones, carries a similar philosophy into the couple’s giving. SUPERCHARGED, she said, is a space where people push each other to level up, mixing community, coaching and real-world guidance. In philanthropy, she is quick to note that many nonprofits are stretched too thin even to hire outside help. “You’re just trying to keep the lights on,” Jones said.

Her solution is what she calls culture, community and capital working in tandem. The community component leverages networks and relationships. Capital is the financial investment. Culture is the part Jones sees as changing hearts and minds. The Jones and Feliciano initiative might also lend its own digital platforms or technology.

At the same time, Jones distinguished the couple’s approach from some typical practices in venture philanthropy, which can involve high levels of involvement by the funder alongside a large capacity-building gift. “We’re not trying to run institutions or organizations by any stretch… but we’ll seed you there and be partners with you there while you’re still going and building the capacity. And we’re not taking it out of the funds we’ve invested in you,” Jones said.

Feliciano said he has learned that multipliers are rarely just about money, but also about finding people with promise and helping them along the way. “The statistic is that only 1% or 2% of the institutional capital out there goes to fund managers [who are] underrepresented minorities,” Feliciano said. “To be honest with you, that statistic is probably worse because if you take out Robert Smith or my firm, the numbers get even worse.”

On the for-profit side of the initiative’s playbook, he estimates it has backed around 20 emerging managers — putting money into firms led by people the couple believes are great investors the market has overlooked. Many have done well. Harlem Capital, cofounded by Harvard MBAs Henri Pierre-Jacques and Jarrid Tingle, has built a portfolio of tech-enabled, post-revenue startups. SoLa Impact, founded by Martin Muoto, combines real estate and social impact investing in South Los Angeles. “…[If] those managers become the next Vista Equitys [Robert Smith’s firm] or Clearlake Capitals of the world, that would be a fantastic part of our legacy,” Feliciano said.

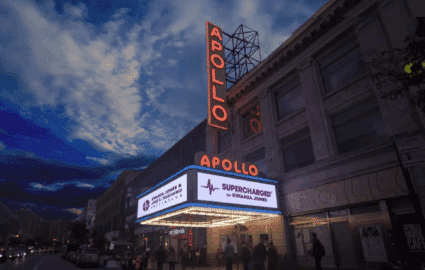

On the nonprofit side, grantees have included PFLAG, which works for the LGBTQ community; Harlem’s historic Apollo Theater, where Jones sits on the board; and Neighborhood Youth Association, which empowers students to achieve 100% college placement and on-time high school graduation.

Jones emphasized that regardless of whether they are working on the nonprofit or for-profit side, values alignment is non-negotiable. That does not mean coercing partners into specific pledges, but it does mean expecting them to contribute to broader social impact efforts. “We’re saying that just as we’re doing this, we need you all to do this, too,” Jones said.

A gift to the Cardozo School of Law strengthens an “impact multiplier”

Jones graduated from Yeshiva University’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 1999. The daughter of lawyers, she never pursued the traditional attorney path, but she never lost sight of what the degree meant. “When I think about what it means to be a lawyer, for me, it’s about being an advocate. Fundamentally, that’s it,” she said, noting that her father worked in immigration and equal opportunity law.

The idea of learning law by practicing it in real communities was what drew her to Cardozo’s clinical model in the first place. Clinics give students the chance to take on the kinds of cases high-profile firms are too busy to touch or would charge too high a retainer for everyday people to afford. “That is that impact multiplier. The investment that we’ve made in Cardozo enables the clinical programs to continue to do great work in the community,” she said.

Jones likes to remind people that the Innocence Project, one of the most consequential legal advocacy organizations of the modern era, was born at Cardozo. It grew out of the law school’s clinical work under Professor Barry Scheck, who cofounded the project and helped pioneer DNA-based exonerations.

Feliciano views the couple’s recent $6 million gift through another lens. He has been thinking a lot about the stories people tell about division. He pointed out that the historically Jewish institution is home to a law school that serves a large and diverse community, and pushed back against narratives of increasing political animosity. “There’s a lot of common history that led to great inroads in terms of civil rights,” he said.

Melanie Leslie, the first Cardozo graduate to serve as dean of the school, described the urgency of training young lawyers to represent people who otherwise fall through the cracks. “There’s a real access to justice problem in this country. People without means can’t afford lawyers, and our public service organizations, while they do a great job, are kind of overwhelmed with the demand,” Leslie said.

At Cardozo, Leslie said, the physical environment has lagged far behind the caliber of the work. But the couple’s donation will help bring the quality of the clinical education space up to the quality of the program.

Rewriting what legacy means at Princeton

In September of 2020, Jones, a member of Princeton University’s Class of 1993, and Feliciano, Princeton ’94, made history with a $20 million contribution to the school. It became the largest gift ever made by Black and Latino donors to Princeton and resulted in two adjoining dormitories bearing their names.

The couple met on campus and Jones’ sister is also an alum, so the roots run deep. The gift helped fuel the university’s effort to widen the student body, including bringing in more diverse populations like Pell Grant recipients and first-generation students. Feliciano admitted that his own Princeton experience was transformative, but also complicated. “Getting there 35 years ago, we didn’t necessarily see ourselves represented in the institution,” he said, recalling that what is now the Carl A. Fields Center for Equality and Cultural Understanding at Princeton was once known as the “Third World Center.”

“For me, having our names… on a building there alongside buildings that might be named for Forbes, Rockefeller, I think that’s extremely important,” Feliciano said. “Because if there’s some kid that comes from Puerto Rico or the Bronx… [that student knows] there are people who have been here before that have excelled and they are part of the fabric of this institution.”

Channeling other philanthropists of color I’ve spoken to, Jones said she wants to expand philanthropy’s understanding of who a donor can be — seeing people of color not just as recipients, but as benefactors. She remembers a mother stopping her to say that her daughter would be living in the dorm named after Jones. Before her name, Jones noted, there had only been one other residential college or dorm named for a woman, Meg Whitman. “It’s easy to get caught in the narrative of Black and brown. But I just think in general, those things are why it makes a difference,” she said.

Jones also helped push to rename Princeton’s former Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, now called the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. She ended up writing what she called a “love letter” to the school, arguing that the aim was not to rewrite history, but to ensure that every student could feel welcome in the spaces where they learned. “It was an opportunity for the university to actually say, ‘we can do something. And we are.’”

Pursuing durability at an at-risk HBCU

Feliciano and Jones’ work has also extended into places where legacy is less gilded and more fragile, like Bennett College, the historically Black women’s liberal arts institution. The Greensboro, North Carolina-based school, which Jones’ mother attended, was fighting for its future, facing accreditation challenges and risking closure. In May 2025, the couple made a $1.5 million philanthropic investment to help stabilize the school’s finances, fund enrollment efforts, and launch new strategic partnerships. Their work joins that of donors like MacKenzie Scott and Arthur Blank, who have also stepped up for HBCUs this year.

Bennett’s president, Suzanne Elise Walsh, who previously worked at the Gates Foundation, praised the couple’s hands-on approach, Jones said. For a pair whose formal philanthropy is only about a decade old, that feedback reassured them that their “supercharged” model was the way to go.

As Jones put it, “Influence without impact is hollow. But impact without influence can be less impactful and can seem almost invisible.” The goal, she said, is to combine the two. “By being able to map impact and influence. That’s how you get the multiplier and leads to more people creating more impact.”